J. Bellemans, J. Oosterbosch, J. Truijen

172

to them, and moreover, this would almost per

definition require some degree of surgical

medial soft tissue release [14-15]. Restoring

the knee to its constitutional alignment by

leaving it in in slight varus and in harmony

with its surrounding soft issue sleeve could

therefore be a more logical option. Recently

published studies seem to confirm this [12-14].

Vanlommel et al noted that preoperative varus

knees that were corrected to their constitutional

alignment did perform better both functionally

as well as subjectively when compared to those

knees that were restored to neutral mechanical

alignment [12].

The debate continues however on which is the

most optimal method to restore constitutional

alignment. In theory several options exist. One

could leave the femoral and/or tibial component

slightly undercorrected, or one could aim for

full anatomic restoration, including the

obliquity of the joint line.

The latter has been popularized as kinematic

alignment reconstruction, during which the

eroded or damaged parts of the knee are

resurfaced to its original anatomic contours.

Today it remains however undetermined

whether one of these strategies is to be

considered superior in terms of functional and

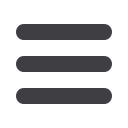

Fig. 1: Histogram depicting the large variability in natural alignment

in healthy male individuals, which contradicts the general belief that

normal alignment is zero. In fact large variability exists between

individuals, and the average alignment in males is around 2° varus.

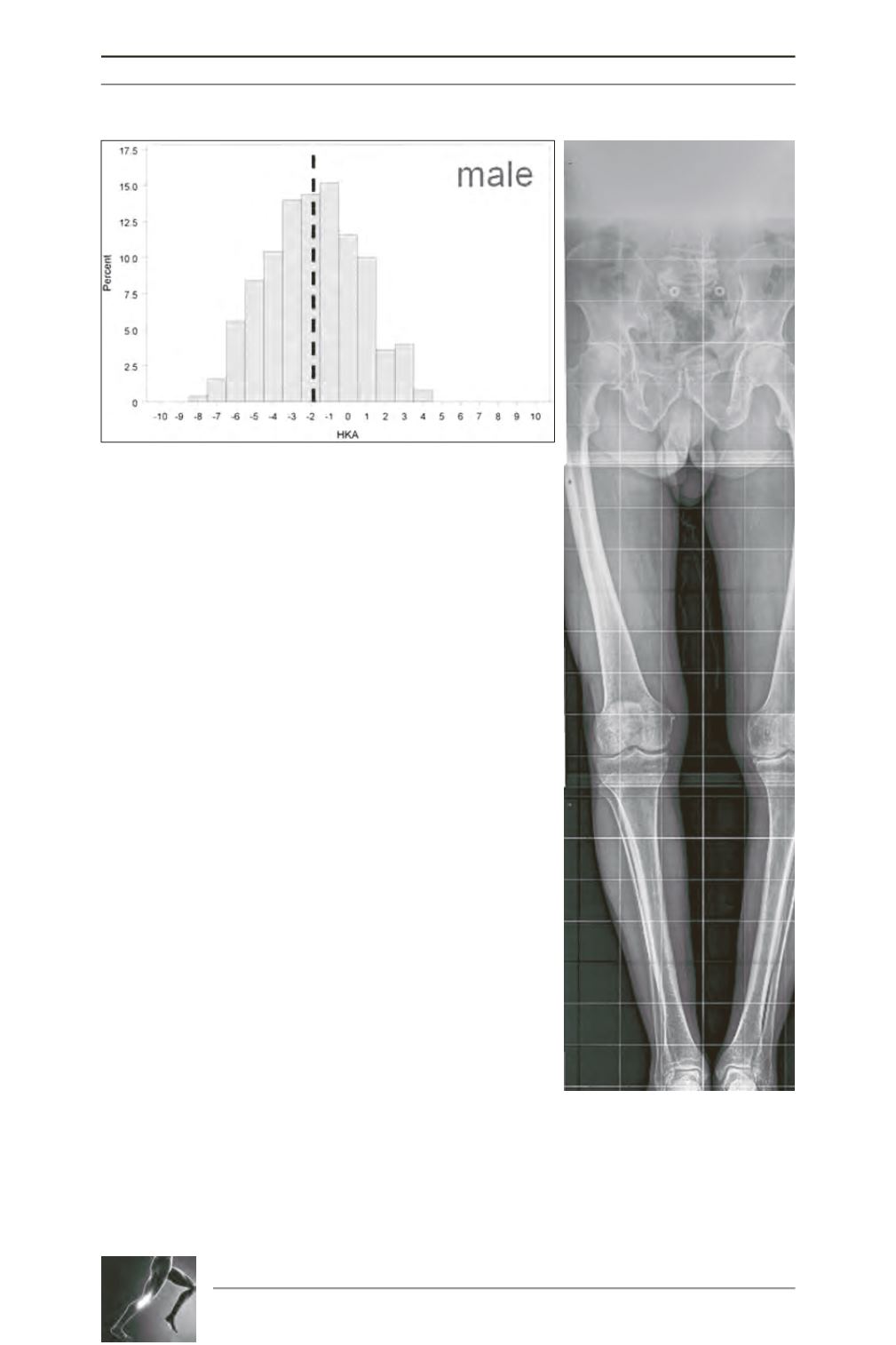

Fig. 2: Typical constitututional

varus knee with medial OA (left)

requiring knee arthroplasty. The

typical characteristics are clearly

shown; varus OA of the knee, varus

hip neck-shaft angle, varus femoral

bowing, and varus of the

unaffected leg.