165

Every surgeon aims to safeguard their patient’s

future. This can be accomplished through two

different strategies: keep doing what one has

always been doing because it works well, or

take some risks to try to make things better.

The purpose of this analysis is not to provide

an unambiguous course of action; instead we

wanted to define the role of cementless total

knee arthroplasty (TKA) based on a review of

literature. We also wanted to define a set of

specifications for cementless TKA.

We are not trying to put cemented TKA – the

current gold standard – on trial. It is safe, can

make up for imperfections in the bone cuts and

has a low rate of loosening over time. In revision

cases, there are fewsurprises except for cemented

long stems. But cemented implants have their

drawbacks: the rare case of cement-related

shock, release of foreign bodies or particles that

can cause premature implant wear. The ageing

of the cement over the long-term also has some

unknowns. And since it takes up and alters the

space made by the bone cuts, it can lead to

stiffness and pain or alter the alignment. Few of

us check the alignment when we apply the

cement, even though navigation systems with

0.5° precision are available. Cement (fig. 1) can

also cause up to a 2° change in the alignment.

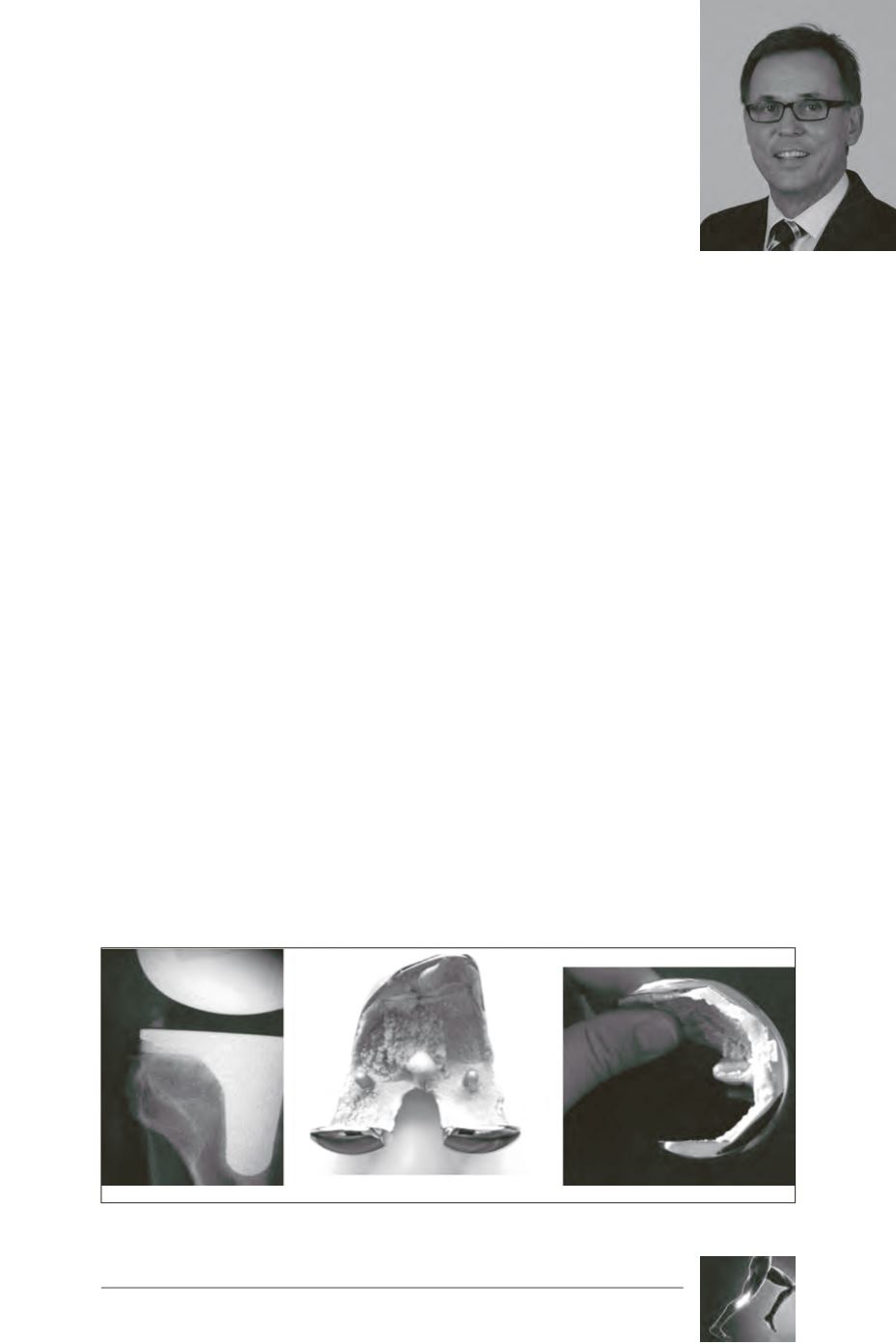

What is the future of cemented implants? An

overly easy explantation (fig. 2) reminds us of

the possibility of problems at the bone-cement

interface.

Strategy: which implant for

which patient?

Specific considerations

about TKA in young patients

Protecting the future: Cemented or cementless

O. Courage, V. Guinet, L. Malekpour

Fig. 1

Fig. 2