E.A. Arendt

370

extremity kinetics. Femoral internal rotation

(IR) and adduction (ADD) in the CKC knee

flexion can contribute to dysfunctional PF

joint loading and tracking [3, 4, 5, 6]. Patients

reporting PF pain demonstrate this frontal

plane collapse with a wide range of CKC

activities [7, 8] (ie) functional or dynamic

knee valgus. This collapse pattern is, in part,

a result of lack of strength and/or activation

of hip external rotators and posterior buttocks

musculature.

Patients should be instructed to resist the

inward collapse of the knees/thighs toward

midline. Often cueing to actively press the

knees/thighs outward is advantageous, with the

focus of “keeping the knee caps over the toes”.

The use of a resistance band around the thighs

can be useful to physically stimulate this

correction with double stance activity. The

degree to which frontal plane mechanics can be

manipulated depends on the patient’s presenting

bony alignment. Long limb torsion, in particular

excessive external tibial torsion, should be

identified by physical exam. The patient should

be allowed to have the toes point in the direction

of comfort when doing this exercise.

Therapy should progress through the re-training

phase from double stance exercises to single

leg partial squats to dynamic activities such as

jump landing from an elevated height (3

meters) or repeated jumping, with the goal

incorporating functional body movement

patterns into the patient’s sport and daily living

activities. Core stability/trunk control should

be both assessed and addressed in the open

kinetic chain (OKC) and CKC states. Lack of

trunk control, particularly in the frontal plane,

has been associated with higher risk of lower

extremity injury, particularly at the knee joint

[9, 10, 11, 12]. Unfortunately there is neither

well-established standardization nor validation

of clinic-friendly core stability testingmeasures.

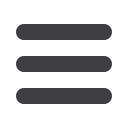

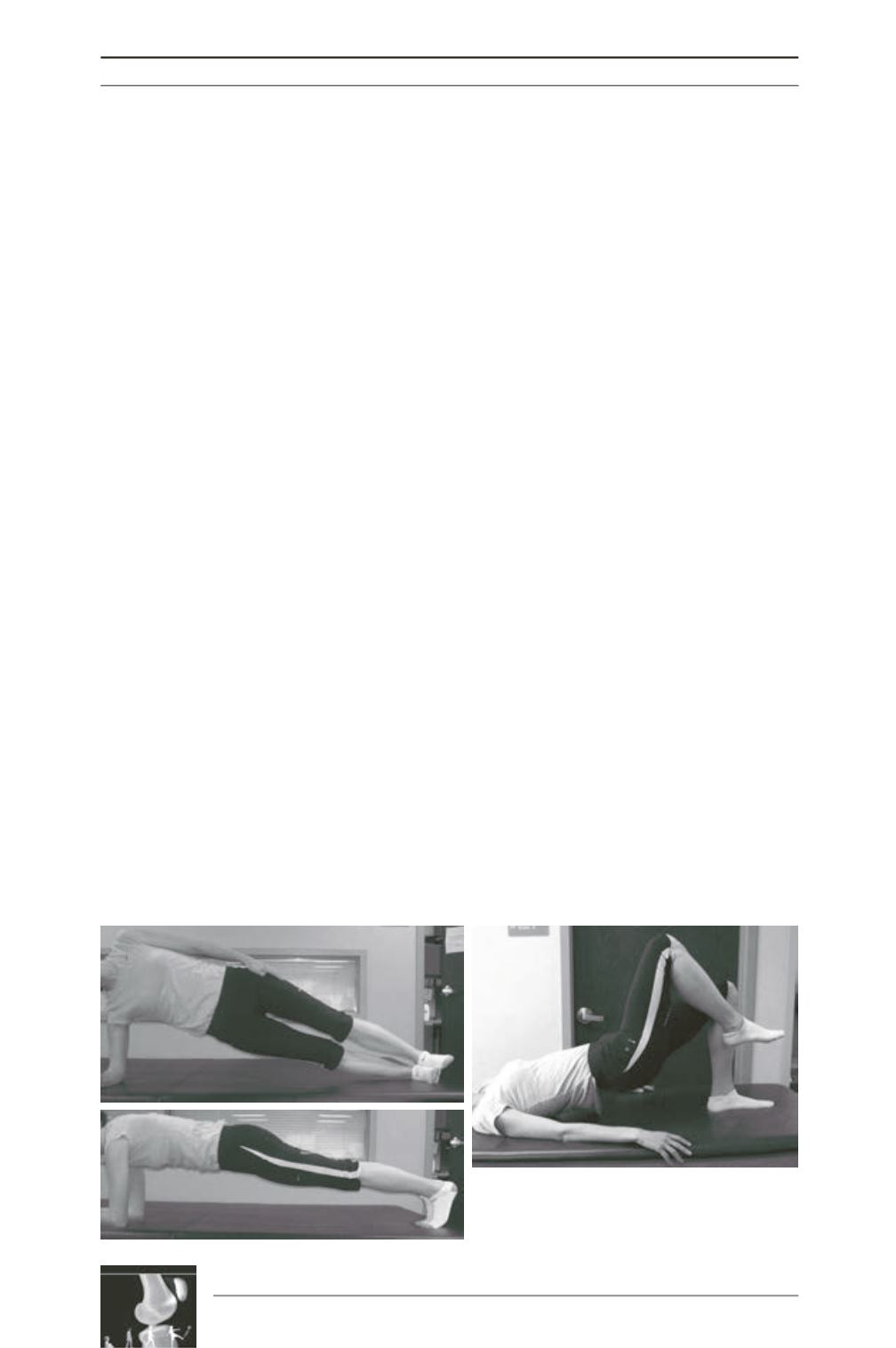

Despite that limitation, core/trunk stability

training, including plank poses in multiple

planes (fig. 3 a,b,c), is broadly viewed as an

important element to establish a foundation for

neuromuscular control as patients progress into

more demanding CKC activities.

“Quadriceps avoidance” movement

pattern with gait

Dysfunction of the PF joint is often associated

with dysfunction of the quadriceps muscle

group, without a clear cause and effect

relationship defined [13]. Patients with chronic

PF pain and/or instability often demonstrate a

gait pattern that avoids deeper knee flexion

during the loading response phase of gait. In

extreme cases, a hyperextension thrust pattern

may be employed, in an attempt to gain knee

stability. Pain from impingement of anterior

knee structures then feeds back into the pattern

of quadriceps avoidance/inhibition [14].

Fig. 3 :

a) Side plank pose

b) Single leg bridge

c) Prone plank pose

a

c

b