W.B. Leadbetter

282

Maquet introduced controversy with his

anterorization tibial tubercle osteotomy for

knee arthritis [13]. Fulkerson improved upon

these concepts with his anteromedialization

tibial tubercle osteotomy (AMZ) [14].

However, despite Radin’s hopes, there was a

growing number of patients who failed to

achieve relief from the available operative

solutions. Total knee arthroplasty was in it’s

infancy and was not considered an option for

the arthritically disabled, often younger (age

less than 50 years old) patient. And so,

beginning in 1974, Blazina launched the

modern age of patellofemoral arthroplasty with

the Richard I and II prostheses. The average

patient age in his series was 39 years (range,

19- 81) [15]. At the same time in France, Cartier

began his series using the both the Richards II

and later the Richards III patellofemoral

prosthesis. As a salvage procedure, these early

experiences were encouraging. In 2005, he

would report on his experience with 70 patients,

average age 60 years (range, 36-81). There was

a prosthetic survivorship of seventy-five

percent at average follow-up of 10 years [16].

Yet, during this period prosthetic replacement

of the patellofemoral joint remained the

unpopular step child of total knee arthroplasty

primarily because of reported high revision

rates due to design deficiencies and difficult

patient selection with regard to risk of

tibiofemoral joint arthritic progression.

We will arbitrarily close this renaissance period

with two developments. The first is the

diagnosis, classification, and treatment impli

cations of trochlear dysplasia. First described

by Ficat and later refined by Henri Dejour,

Phillipe Neyret, and David Dejour, the

recognition of trochlear dyplasia proved to

have significant implications for both the

successful long term outcome and prosthetic

evolution of patellofemoral prosthetic design

[17, 18]. Argenson called attention to the

presence of trochlear dyplasia as a key factor in

predicting the success of patellofemoral

arthroplasty with respect to progressive

tibiofemoral joint involvement. It was theorized

that because this mechanical cause of premature

patellofemoral degeneration seemed indepen

dent of more genetically predisposed tricom

partment arthritis, patellofemoral dysplasia

would tend to be a marker for the selection of

thesocalledisolatedpatellofemoralarthroplasty

case [19]. Others would agree [20, 21]. The

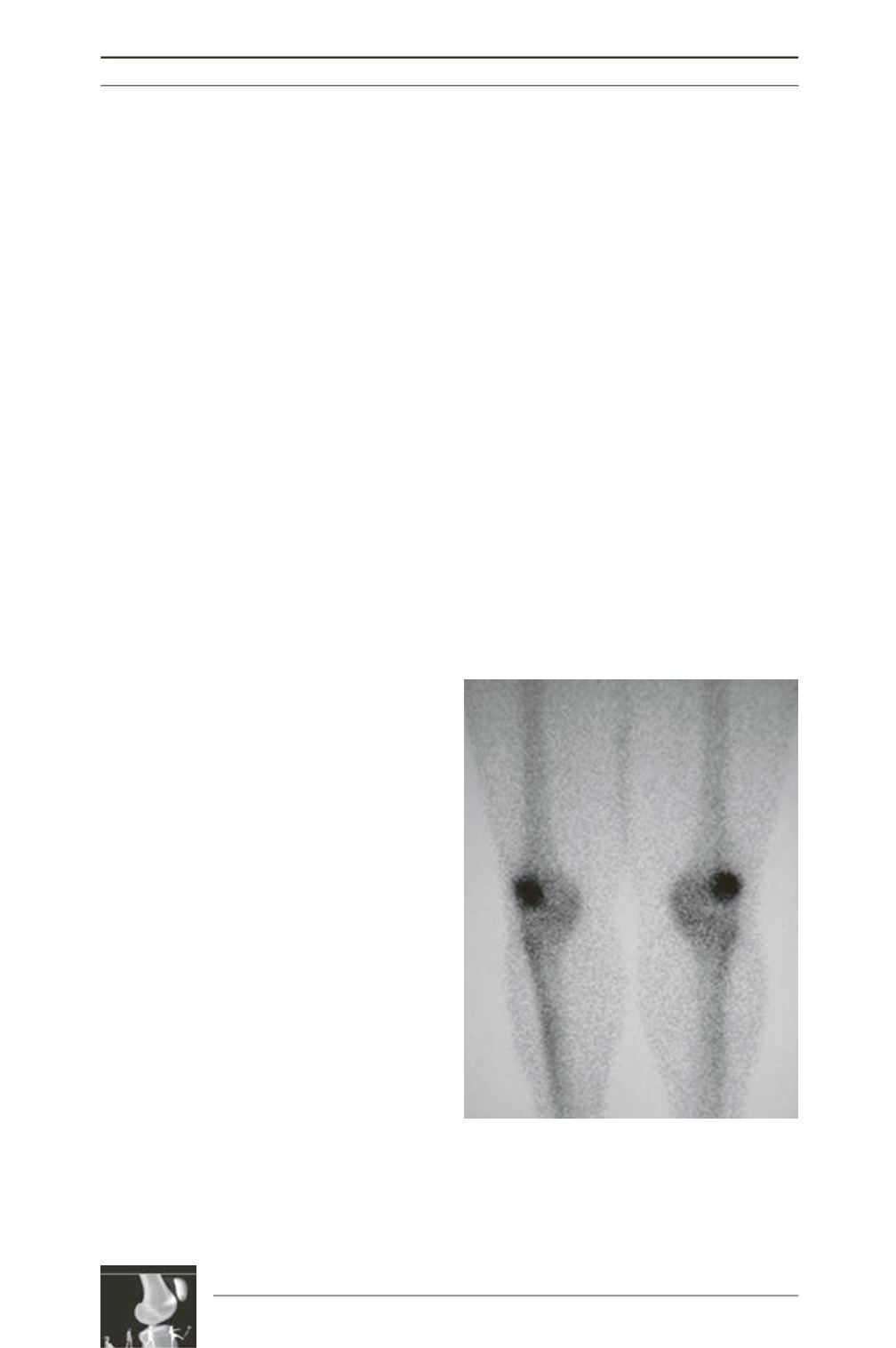

second development was Dye’s recognition

that radionuclear bone imaging could be a

useful tool in dynamically visualizing Wolf’s

Law. His concept of the comfortable knee and

patellofemoral joint functioning in a

homeostatic load/use envelope and the

association of patellofemoral pain with

supraphysiologic load in the absence of other

structural damage helped clarify an old dilemma

as to why isolated chondromalacia was not

always symptomatic [22] (fig. C). As a

corollary, while an inactive nuclear bone scan

can be seen in the painful degenerative

patellofemoral joint, an active nuclear bone

scan is not pathognomonic of a degenerative

diagnosis as some would claim.

Fig. C: Typical radionucleotide scan revealing loss

of bone homeostasis of the patellae. Plain

radiographs were normal; however, such patients

may or may not have patellofemoral degeneration.