W.B. Leadbetter

280

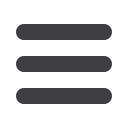

associated with aging, although the two tissue

pathologies are similar, but not entirely identical

[3]. Hence, young patients (a class increasingly

difficult to define) may display premature

patellofemoral wear. In 1908, Budinger excised

degenerative patella articular chondral tissue

which he described as “chondropathy” (fig. A).

In 1928, Aleman from Scandanavia refined this

physical description in the operating room as

“chondromalacia patella post-traumatica”, a

post injury softening of the patellar articular

surface [1]. Cadaveric studies of Owre (1936)

and Hirsch (1941) would introduce the term,

“chondromalacia patellae” as a unique entity

[4]. No long after, Cox (1945) and Bronitsky

(1947) would include patella cartilage

fibrillation and softening in the potential causes

of patellofemoral pain syndromes [4].

Chondromalacia patellae would become

synonymous with patellofemoral arthralgia.

Lacking insight into the functional cost of

patellectomy and the secondary deleterious

effects on tibiofemoral joint durability, standard

of care drifted toward a “when in doubt, cut it

out” salvage for the damaged patella. Despite

isolated satisfactory outcomes, patellectomy

did not account for pain arising from trochlea

disease and there was a significant pattern of

persistent impairment after patellectomy [5].

Otherwise, in many ways, it was the age of the

“forgotten patella”.

That said, some surgeons were impressed

enough with the disability of patellofemoral

degenerative wear to advocate patella

resurfacing with skin, fat pad, or fascia.

In 1955, the earliest attempt at prosthetic

replacement of the degenerative patella surface

was reported by McKeever [6] (fig. B). This

metal hemiarthroplasty was used sparingly with

improvements by Worrell. Primitive design and

inherent failure of the trochlea cartilage surface

limited its application. The idea would not be

seriously reconsidered until 1979.

The Age of Awakening- the

Patellofemoral Renaissance (circa

1960s-early 1990’s)

A resurgence in surgical interest in salvaging

the painful patellofemoral joint began to stir in

the 1960’s. With the publication of their article

on the diagnosis and treatment for recurrent

patellofemoral instability, Trillat and Dejour

called attention to the importance of extensor

malalignment as a source of anterior knee pain

and its potential correction by redirection [7].

Hughston was another early voice, commenting

in 1960 and reiterating in 1984 that recurrent

subluxation of the patella was often overlooked

in the diagnosis of medial knee joint pain [8].

Shortly after, a young American graduate

Fig. A: Chondromalacia patellae (arthroscopic

view): Often treated by the euphemistic method of

chondroplasty. While studies have shown short

term relief of pain, functional improvement is

unpredictable. The concept is limited in the same

way that mowing a lawn down to dirt can eliminate

weeds, ie nonrestorative.

Fig. B: McKeever prosthesis