D.C. Fithian

94

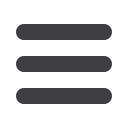

As the clinician develops an understanding of

the symptoms and complaints, he or she can

begin to develop one or more hypotheses,

which can be tested in the physical examination

and with subsequent imaging studies. The

isolated complaint of pain, with no objective

findings to suggest a specific source (pathology)

representing an indication for surgery, should

be treated nonoperatively.

Physical examination

Due to the complex and delicate interactions

between the knee extensor system and lower

limb function, clinical evaluation of patello

femoral complaints can be challenging. After

other disorders have been ruled out, specific

testing for disorders of the patellofemoral joint

can be performed. The patient should be

evaluated standing, walking, and stepping up

and down from a small step, squatting, sitting,

supine, running, and jumping. Observation of

the patient during a few functional activities

yields a great deal of information about patello

femoral loading and neuromuscular condi

tioning (fig. 1). Any hindfoot valgus, forefoot

pronation, and/or heel cord tightness should be

noted as they can affect tibial rotation and

patellofemoral alignment [1].

The prone position allows estimation of several

important variables, including quadriceps

tightness (important if correction of patella alta

is being considered), femoral internal and

external rotation limits, and foot-thigh angle

(FTA) and/or trans-maleolar axis (TMA)

(fig. 2). Femoral and tibial rotation can be

estimated by examining the patient prone with

the hips extended, the knees flexed 90°, and the

feet and ankles in a neutral, comfortable

position with the soles of the feet parallel to the

floor after the method of Staheli

et al.

[2]. Kozic

et [3] showed that on physical examination,

femoral anteversion should be suspected if

prone hip internal rotation exceeds external

rotation by at least 45 degrees. With respect to

estimating FTA and TMA, Staheli reported a

wide range of normal values, with mean values

of 10° for FTA and 20° for TMA [2]. Souza and

Powers also confirmed the reliability of the

Staheli method for estimating femoral

anteversion, though axial imaging was more

precise [4]. Our preferred approach is to use the

prone physical examination to screen for torsion

of the tibia and femur, and to obtain CT scan to

assess rotational alignment if hip IR exceeds

ER by at least 20 degrees or if the prone foot-

thigh axis or TMA is greater than 20 degrees.

The lines of action of the quadriceps and the

patellar tendon are not collinear. The angular

difference between the two is the quadriceps

angle, or “Q-angle”. Because of this angle, the

force generated by the quadriceps serves to

both extend the knee and to drive the patella

laterally, compressing the femoral trochlea in

order to convert tension in the quadriceps into

extension torque at the knee. The relative

magnitude of the laterally directed force is

related to the Q-angle. External rotation of the

tibia, internal rotation of the femur, and

increasing knee valgus all cause an increase in

the Q-angle and thus an increase in the laterally

directed force within the PFJ (fig. 3) [1].

Fig. 1: The step-down test is a simple test that can be

done in the clinic to evaluate core and hip control.

This patient demonstrates pelvic weakness with hip

adduction and medial collapse of the knee. It is

apparent that her weakness results in a variety of

functional alignment abnormalities, including: (1)

contralateral pelvic drop, (2) right femoral internal

rotation, (3) right knee valgus, (4) right tibia internal

rotation, and (5) right foot pronation.