In recent times, technological progress allo-

wed more advanced tools to be used, including

in vitro studies with MRI on cadaveric speci-

mens [8, 9], in vivo analyses using 2D fluoro-

scopy with shape matching techniques, based

on CT models [10-13], roentgen stereo photo-

grammetric analysis [14] and open dual coil

MRI’s [15-17]. These newer methods revealed

a more complete, three-dimensional insight in

the morphology and kinematic patterns of the

normal knee in loaded and unloaded condi-

tions. Nevertheless, correct description of knee

kinematics, allowing clinical applications,

remains a major challenge: as Kinzel and

Gutkowski stated, “the unambiguous descrip-

tion of spatial motion is perhaps more difficult

than the measurement” [18].

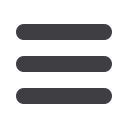

For reasons of practical understanding and cli-

nical application, knee kinematics are current-

ly often presented as the projection of the

centre of the femoral condyles onto the hori-

zontal plane of the tibia, as a function of the

flexion angle (fig. 1).

This presentation of kinematics gives a good

intuitive understanding of the motion between

tibia and femur but it is important to unders-

tand that it is a simplification of a complex

three dimensional motion. Neither is this pre-

sentation identical to the imaging of tibiofe-

moral contact points. The latter technique is

most often used for the description of kinema-

tics after TKA. Based on single perspective

video imaging, a model fitting process allows

to determine the relative three dimensional

position of the implants (fig 2). The presumed

tibiofemoral contact point is derived from a

calculation that determines the shortest distan-

ce between the tibia and the femur.

14

es

JOURNÉES LYONNAISES DE CHIRURGIE DU GENOU

166

Fig. 1 :

a) Projection of the centre of the femoral condyle

onto the horizontal plane of the tibia [19].

b) Lines connecting the projected points as a func-

tion of the flexion angle.

a

b