The Principles of an Ideal Patellofemoral Arthroplasty

295

Trochlear Component

It is not uncommon for patients with isolated

patellofemoral arthritis to have associated

abnormal

patellofemoral

biomechanics.

Trochlear dysplasia combinedwith an increased

tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance [22]

results in increased pressure on the lateral

aspect of the patellofemoral joint. This

predisposes the patella to sublux laterally. A

trochlear prosthesis with a steep, relatively

long prominent lateral facet would prevent the

patella subluxing, ensure contact in full

extension and engagement of the patella in

early knee flexion. If the lateral facet is too

prominent soft tissue impingement will occur,

therefore a balance must be found between

constraint and conformity.

In mid knee flexion, internal rotation of the

tibia will have reduced the Q angle and

consequently the lateral force, whilst the

posterior force is increased due to the angle

closing between the quadriceps and patellar

tendon in the sagittal plane. During this range

of movement the patellar component should be

stable; a trochlear component with a single

radius of curvature is sufficient to allow this

motion to take place effectively. The trochlear

component should fit flush over all aspects of

contact with the distal femur, avoiding the need

to place it in flexion or hyperextension, where

it will catch the patella or impinge onto the

anterior cruciate ligaments, respectively [23].

In deep knee flexion the patellar component

articulates with the articular surfaces of the

femoral condyles. The transition point from

prosthesis to articular cartilage must be even to

avoid any catching of the patella. All current

prostheses extend to the intercondylar notch

but not beyond. There is an assumption that the

articular cartilage adjacent to the prosthesis is

normal, however this is not true for all cases. A

wider distal endmay provide adequate coverage

for the more extensive wear patterns but

potentially at the expense of damage to the

menisci when the knee is extended, and

preventing the later addition of a unicom

partmental arthroplasty in the presence of

progression of tibiofemoral arthritis. This

means that the patellar component must be

compatible with the articular cartilage.

In the native knee the trochlea is asymmetrical.

The lateral articular facet is approximately

50% larger than the medial to accommodate

the higher load. It therefore seems logical that a

femoral component should mimic this

geometry, particularly when considering a

significant number of patients will have a

history of patellar instability with a tendency to

track laterally.

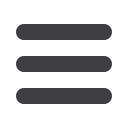

A

B

Fig. 6 : Forces acting on the patella in the sagittal plane. Quadriceps tension (Q), patellar tendon tension

(PT) and joint force (JF). The JF moves proximally across the patella as the knee flexes, rising significantly

with increase in knee flexion for the same PT.

Permission to use image granted by copyright owners Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Amis AA, Senavongse W,

Darcy P. Biomechanics of patellofemoral joint prostheses. Clin Orthop 2005; 436: 20-9.