M. Thaunat, C. Bessiere, N. Pujol, P. Boisrenoult, P Beaufils

206

isolated and associated abnormalities were

always corrected in the same surgical step. We

think, however, that correcting trochlear depth

abnormality plays a major role in stabilizing

the patella by facilitating proper entrance of the

patella into the trochlea. Depression

trochleoplasty was found to enable PTA

correction even when the MPFL was not

reconstructed, and is effective in revision when

other procedures had failed, as reported by

Goutallier

et al.

[6]. Thus, MPFL reconstruction

should not be necessary when recession wedge

trochleoplasty has been performed, as the

reduction in trochlear prominence prevents

lateral misdirection and facilitates patellar

sliding into the trochlear recess. The instability

recurrence rate of around 10% (n=2) in the

present series was acceptable, given that in 1 of

the cases trauma was implicated in the recurrent

patellar dislocation, and the other was a difficult

multi-operated knee in which three previous

stabilization procedures had already failed.

Deepening trochleoplasty is often not attempted

because of surgeons' limited familiarity with

this demanding surgical technique. There is,

moreover, no reliable landmark to determine

where to locate the new trochlear groove. In

comparison, recession wedge trochleoplasty

requires assessment of the abnormal geometry,

but is not difficult to master. Wedge recession

is identical in principle to deepening

trochleoplasty, except that a wedge rather than

a trench of bone is removed so as to create a

new sulcus. It was first described by Goutallier

and early results were encouraging [6]. The

aim is to lower the subchondral bone of the

trochlear groove at the anterior cortex of the

femoral shaft without modifying its shape.

A study performed on fetuses by Glard

et al.

suggested that the anatomic characteristics of

the patellar groove were integrated into the

genome during the course of evolution [22].

This would be in favor of a genetic origin for

patellar groove dysplasia. Postnatally, the

position of the patella in relation to the trochlea

plays a major role in the final shape of the

patella and trochlea, which develop congruent

articulating surfaces [23, 24]. Moreover, there

is a difference between the bony and cartilage

morphology of the patellofemoral joint [25,

26], so that congruent cartilaginous articulation

maycoexistwithunderlyingbonyincongruence.

From this point of view, lowering without

deepening the groove facilitates the entry of the

patella into its groove with respect to

patellofemoral congruence. The aim of the

procedure is to diminish the central bump

responsible for patellar misdirection and lateral

subluxation and to guarantee adequate trochlear

depth, and maximal hyaline cartilage

conservation without affecting patellofemoral

cartilage congruence.

The risks associated with deepening trochleo

plasty include breaking the osteochondral flap,

distal detachment, and excessive thinning of

the flap, decreasing blood supply. There are

also concerns about articular cartilage viability

following trochleoplasty. Recession wedge

trochleoplasty should decrease the risk of

chondral damage and necrosis. Since the

dysplastic segment of the trochlea is lifted as a

single osteochondral block and there is no need

to fashion a new groove by cutting the

osteochondral flap, it is possible to conserve

more subchondral bone, thus decreasing the

risk of possible severe irreversible articular and

subchondral injury, especially in older patients

where cartilage is less flexible. Moreover, the

wedge and trochlear recess are flat and

complementary, whereas in deepening trochleo

plasty, the osteochondral flap might not tally

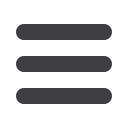

Table 4: Literature review: trochleoplasty for major dysplastic trochlea.